Author: Maslyayev Alexander , published: 04/2017, https://habr.com/ru/post/403225/

Spring is an interesting time of year, and it should be celebrated properly. A deep, heavy, multi-part debate about the essence of information is, in my opinion, a pretty good way to celebrate spring on GeekTimes.

I apologize in advance for the fact that this will be quite lengthy. The topic is extremely complex, multifaceted, and remarkably neglected. I would love to condense everything into a short article, but that would inevitably result in a shoddy piece with glaring logical gaps, vague questions, and truncated storylines. Therefore, I invite the esteemed audience to be a bit patient, get comfortable, and enjoy a thoughtful and calm exploration of issues that have long been shrouded in mystery.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Right now, as this text is being written, a rather amusing situation has arisen. Society has rapidly entered the information age, but the worldview used to understand what is happening has, at best, been inherited from the early industrial era. There is currently no widely accepted way to incorporate the concept of “information” into our worldview in a manner that does not contradict the phenomena we clearly and universally observe.

We have become quite adept at gathering information, storing it, transmitting it, processing it, and utilizing it. To be fair, we all know very well what information is. However, this knowledge is implicit. Implicit knowledge is an understanding that is taken for granted, which is fine for internal use but inadequate for productive collective use.

The tasks of the philosophy of information:

- Identify and eliminate the obstacles that hinder the translation of “information” from implicit knowledge to explicit knowledge.

- To create a metaphysical system that can organically and coherently incorporate the informational processes that have already become a part of our daily lives.

In my further exposition, I will proceed from the idea that philosophy is primarily a tool for shaping conceptual frameworks and the rules for their use. This differs somewhat from what is typically meant when the word “philosophy” is mentioned. It is often believed that philosophy should provide answers to questions about the existence of things and clarify some of the most general laws of the universe. However, it often turns out that before we begin to ponder the nature of the universe, it is useful to develop a language that ensures these reflections are not inherently meaningless.

It is precisely the task of forming language, rather than the search for Truth, that will constitute…the basis of the methodI will try to adhere to this in the following narrative. To clearly demonstrate this method, I will provide several examples, including those from related areas of philosophy:

- Does God exist?

The question is methodologically incorrect (according to the applied basis of the method). The correct formulation is:How should one think about God in order for those thoughts to be meaningful? - Are there objective laws that govern the world?

Correct wording:How should we talk about the existence of the laws of the universe so that it doesn’t become a waste of time? - What is primary – matter or consciousness?

Correct wording:How should we talk about primacy, matter, and consciousness so that our words are not just a meaningless pastime? - What is information?

Correct wording:How should we think about information so that our reasoning makes sense?

We should assume that the philosophy of information should become the adequate linguistic tool that meets our needs, allowing us to avoid logical dead ends every time we discuss the nature of information, consciousness, management, system formation, complexity, and other topics that have become heavily mythologized.

To vividly demonstrate the power of the instrumental approach, it is appropriate to provide the following historical illustration. Long ago, the question of whether the Earth revolves around the Sun or the Sun revolves around the Earth was a highly contentious dilemma. It even reached the point where physical reprisals against ideological opponents were common practice. Now, having learned to reason about motion and understanding that the key aspect of these discussions is the choice of the observer’s position, we have the opportunity to use the heliocentric system for our convenience when discussing the structure of our planetary system, while in our everyday affairs, we can rely on the geocentric system. When we say that the Sun rises in the east and sets in the west, we implicitly suggest that the Sun is moving, even though from the heliocentric perspective, this is false. The difference between what was and what is now lies only in the fact that we have acquired a conceptual framework that allows us to reason about motion more adequately. The ability to channel discussions into a constructive direction, thereby reconciling opposing positions, is not the only useful function of the instrumental approach. Another valuable function is the enforced closure of those problems for which it becomes evident that there are no meaningful ways to reason about them.

The instrumental approach to philosophy certainly has its limitations. In particular, the question of how to distinguish productive reasoning from unproductive reasoning must remain open and subject to discussion. One could emphasize logical consistency or practical usefulness, but both are rather vague criteria. It seems to me that we can only hope that discussions about the usefulness of things are usually much simpler and more productive than discussions about the existence of things that no one can confirm or refute. After all, usefulness is precisely the kind of thing that lends itself best to a vote with one’s feet.

I do not want to suggest in any way that the instrumental approach is my invention. It has been described in a vast number of philosophical texts and is used productively in even more. This, in itself, is an obvious point that had to be highlighted in the introduction simply because if we do not emphasize it beforehand, much of what follows may seem wild and at times self-contradictory. The specificity of the task is such that it is impossible to remain within the bounds of basic truths and familiar logical constructs. I will reiterate: we will not be searching for eternal and unchanging Truths-with-a-capital-T, but rather we will attempt to find a language in which discussions about information, systems, and management do not lead us into a logical dead end at every turn.

A brief history of the issue

This section does not aim to systematically present the history of global philosophical thought. The goal is merely to provide some context for the subsequent discussions, as they cannot be understood or accepted without it.

Plot one: materialism vs. idealism

Materialists have believed and continue to believe that only physical reality truly exists (in Democritus’s words, “atoms and void”). Accordingly, what we can observe as ideas is merely a movement of atoms in the void that occurs in some mysterious “special way.” The nature of this “special way” is usually not specified, and when there is an attempt to clarify this question, at best, a clumsy quote from a school physics textbook is provided.

Idealists believed and still believe that only ideas truly exist, while what we perceive as the surrounding coarse physical reality is either an illusion or the result of sorcery.

Arguments for and against these viewpoints are numerous, diverse, and all extremely weak, even though in the 20th century materialists have experimentally confirmed millions of times that if a person is kept locked up and not fed, they stop thinking about ideas and start thinking about food.

There is an opinion (particularly expressed by Merab Mamardashvili in “Introduction to Philosophy”) that true philosophers have never seriously considered the question of whether consciousness or matter is primary. If we approach this so-called “fundamental question of philosophy” from the perspective of the instrumental approach to philosophizing that I described in the introduction, an interesting point emerges. For either a discussion of the existence of matter without implying the presence of consciousness, even in the form of an implicit observer, or a consideration of the functioning of consciousness without its material realization to have any meaning, we must be able to find ourselves in a situation of either the absence of consciousness or the absence of matter. Both scenarios are impossible, and therefore no discussion of primacy can be meaningful. Thus, when applied to the question of primacy…“How should one think about…?”receives a response“Not at all”Текст для перевода: ..

For our purposes, perhaps the most valuable outcome of the discussion between materialists and idealists is the very framing of the question regarding the existence of material and immaterial entities. In particular, the division of the world into extended things (res extensa) and thinking things (res cogitans), introduced by René Descartes, has proven to be quite useful and productive. As long as humanity focused its practical activities on studying and creating extended things separately, and on operating with thinking things separately, this division of the world did not pose significant inconveniences and was merely a theoretical issue that could be resolved later when the opportunity arose. With the advent of the information technology era, we have learned to create material (res extensa) things that are entirely designed for manipulating immaterial (res cogitans) entities, and thus the qualitative integration of these divided worlds has become a task that philosophy of information cannot afford to overlook.

Plot two: the search for the foundations of reliable knowledge.

The search for the foundations of reliable knowledge runs like a red thread through all of European philosophy. From the perspective of practical utility, this theme has proven to be the most fruitful, providing the basis for the scientific method and, as a consequence, giving rise to all the technological wonders that we have the opportunity to enjoy.

The central idea underlying the justification is the concept of objective reality as perceived by a perceiving subject. Each time we discuss the existence of something in objective reality, it is necessary, for the sake of methodological accuracy, to define the subject that perceives this reality.

The topic of the “perceiving subject” has been thoroughly explored by existing philosophical traditions and could serve as a good starting point for the philosophy of information, were it not for two significant points:

- The perceiving subject is a passive being. It perceives objective reality and acquires reliable knowledge.information) about it, but in discussions about what information is, the concept of the perceiving subject cannot serve as a starting point, because it already includes the concept of information. Essentially, “information” turns out to be a concept that we have jumped over in order to move forward. Therefore, we need to dig a little deeper, and we should build subjectology not from the perceiving subject, but from something else. In particular, we will further introducea purposefully acting subject, which does not just “reflect” objective reality, but lives within it, and information is needed not just for the sake of “reflection,” but for some purpose.Text for translation: purpose.By setting aside the topic of “the subject’s goals” and considering the presence of goals as something self-evident and not up for discussion, it becomes impossible to talk about the meaning of information. And meaningless information is not information at all.

- The perceiving subject is an infinitely lonely being. The entire world surrounding the perceiving subject is an objective reality for them. Even those objects with which the perceiving subject senses a fundamental affinity are not subjects to them, but rather objects about which they strive to gain reliable knowledge. From the perspective of information philosophy, such a neat yet sad picture of the world is completely unacceptable, as it does not allow for communication between subjects. Communication requires at least two subjects, but in a worldview divided into two parts—the perceiving subject and the reality perceived by them—the subject is, by definition, alone. We are simply forced to move away from the old, cozy concept of the thinking (and therefore existing) perceiving subject. Let us try not to get lost.

Having lost the usual way of deriving the foundations of reliable knowledge from the concept of the “perceiving subject,” we will be forced to find an adequate replacement. Otherwise, the resulting metaphysical system will lack justification and, therefore, will not be suitable for use.

Plot three: determinism vs. free will

It so happens that from the perspective of the philosophical foundation of natural scientific knowledge (epistemology), objective reality is structured in such a way that there is no room for free will. The most that exists is randomness (in particular, quantum uncertainty), from which free will cannot be derived in any way. On the other hand, for moral philosophy (axiology), the existence of free will is a necessary condition. Moreover, the existence of free will can be quite easily derived directly from “I think, therefore I am,” which adds a certain piquancy, since the foundation of natural scientific knowledge is also derived not from nowhere, but from the very same primary fact, “I think, therefore I am.”

In short, we will try to extricate ourselves from the resulting true antinomy by eliminating the passivity of the perceiving subject. By acting in the world, the subject will inevitably become a part of it, which will allow us to have determinism in those aspects that the subject does not influence, while maintaining free will in the nature and outcomes of their actions.

The problem of “determinism vs. free will” is a good opportunity to discuss the nature of causality, as determinism is the predetermination established by the rigidity of cause-and-effect relationships.

When discussing a purposefully acting subject, it is impossible (and unnecessary) to overlook the conversation about how it is even possible for causal relationships to exist in our world.

Plot four: Turing machine

In the second half of the 20th century, philosophers were given a fascinating toy—the Turing machine, which can perform any computable calculation. Since brain activity is viewed as information processing, or computation, it follows that either a Turing-complete computer can be taught to think in a truly human way, or we must accept that there is some unexplored secret component in thinking, which inevitably leads to mysticism. This could be traditional mysticism (God), non-traditional mysticism (information fields), or pseudoscientific mysticism (attempts to latch onto quantum uncertainty).

Mysticism is an attempt to explain the unknown through the inherently unknowable. It’s pure trickery. We won’t do that. But we will also demonstrate the unfeasibility of human thought as a Turing-complete computation. For this, we just need to learn to think a bit more adequately about information and its processing.

Chapter 1. Dualism

The metaphor “book”

Examining a book, a regular paper book, which is still a fairly common item in our daily lives, will help us understand how the material and the ideal intertwine into a single whole.

From one perspective, a book is a physical object. It has mass, volume, and occupies a certain space (for example, on a shelf). It has chemical properties, and in particular, it burns quite well.

From another perspective, a book is an immaterial object. It is information. When talking about a book, one can discuss the plot and the relationships between characters (if it is fiction), the accuracy of the facts presented (if it recounts real events), the depth of the theme explored, and other aspects that certainly have neither mass nor chemical properties.

Let’s take the tragedy of William Shakespeare, “Hamlet,” as an example. Imagine you have this book in your hand. Naturally, you are holding a physical object. The plot of “Hamlet” cannot be grasped in your hand. The book isn’t very thick, and it doesn’t weigh much. The pages have a pleasant smell. You could conduct a chemical analysis and find that this object is primarily made of cellulose, with traces of ink, glue, and other substances. In a solid state, it doesn’t differ much from a pulp novel sitting next to it on the shelf. But it is quite clear that this object contains something beyond atoms. Let’s try to find it. We take a microscope and look closely. We see the interweaving of glued wood fibers and their connection to bits of ink. If we use a more powerful microscope, we will see many interesting things. But all this interesting stuff will have nothing to do with “to be or not to be,” nor with the idea of revenge for betrayal and murder. No matter how much we investigate the material component of the book, we won’t find the informational aspect. Just atoms and emptiness. Yet, it is absolutely accurate to say that “Hamlet” contains a plot, characters, and the famous “to be or not to be.” And to discover this, you don’t need a microscope at all. You just need to open the book and start reading. Interestingly, from an informational perspective, the material layer fades into the background so much that it doesn’t matter whether the book is made of paper or, say, parchment. After all, “Hamlet” can also be read on an e-reader, where there are definitely no wood fibers with bits of ink stuck to them.

So, we have two ways of looking at the book “Hamlet”: a materialistic approach, where you can see everything except the idea, and an idealistic approach, where the interweaving of fibers is completely unimportant, but the interweaving of the plot is what matters. And yet, the subject remains the same. The only difference is in our own approach to it. That is, in what we intend to do with it – weigh it or read it. If we plan to weigh it, then we have a completely material object before us, but if we plan to read it, then we are dealing with a completely immaterial essence.

A reasonable question arises: is it possible to somehow manage to look at this subject in such a way that we can simultaneously see both of its aspects? Yes, it is possible and necessary, but I can’t say that it’s easy. It’s very challenging. It requires significant effort and the use of a whole arsenal of tools and techniques, which I will try to explain further. This is important at least because the ways of reconciling the objective and subjective into a unified whole form the metaphysical foundation of the philosophy of information. However, before we start merging the aspects of reality, it will be useful to understand the depth of the problem.

The totality of physical reality

The concept of “material” can be defined in various ways. For example:

- Everything that exists objectively. This interpretation is directly or indirectly used by the classics of materialism. For example, Lenin wrote that objective existence is a function of matter. For the philosophy of information, this approach is unsuitable primarily because it either immediately materializes informational entities or deprives them of the right to objective existence. In the first case, we fall into the trap of reification (which we will discuss below), and in the second case, we find ourselves at an impasse when faced with the simplest, easily observable phenomena. For instance, try to add a happy ending to “Hamlet” in such a way that it no longer ceases to be “Hamlet.” Or, as another option, change the thousandth digit in the number “pi.” Both are ideal entities, but something overwhelmingly strong keeps them anchored in objective reality.

- Everything that is different from the mental and spiritual. This definition is inadequate because we still do not know what the mental and spiritual are. In other words, informational. At this point in the narrative, we are not yet able to reason about information, and therefore we cannot make decisions about what constitutes an informational entity and what does not.

- Everything that exists in physical space. That is, what Descartes defined as “res extensa.” Bodies are extended. If you take a closer look at what physics studies, it becomes clear that all entities described by it are, in one way or another, tied to the painfully familiar three-dimensional physical space. When talking about mass, it is impossible to abstract from its location. When discussing a field, one cannot avoid talking about the distribution of its characteristics in space. When speaking of energy, it is impossible to remain silent about what exactly possesses this energy – a physical object (something localized in space, at least as a wave function) or a field, which also cannot be conceived apart from space. There is a certain temptation to tie ourselves not only to space but also to time, but we will refrain from doing so, if only because there is a wonderful section in physics called statics, which manages perfectly well without the concept of “time.”

Thus, localization in physical space serves as a one-to-one method for defining the materiality of an object.

Physical space is an omnipresent thing. Everything we deal with around us exists within it. Simply because it is, by definition, all around us. Space is infinite in all directions and has no gaps that we could stumble upon.

Wherever you go, wherever you look, whatever you touch – all of this exists in an infinite physical space, both in width and depth. Even if things like teleportation or, say, interdimensional travel become a reality, it won’t change anything. A teleported brick still needs to occupy a space in order to exist after it has arrived “from nowhere.” No matter what fairy tale we come up with, no matter how we spur the horses of our imagination, if there are any tangible objects in that tale, our omnipresent physical space is always present.

Even when discussing the curvature of space or the idea that it actually has more than three dimensions, it doesn’t change anything. It merely clarifies the properties of the “grid” within which we must localize the existence of objects. The amusing fact from the theory of relativity that the “grid step” depends on the observer’s speed also just adds a correction to the methodology of using the “grid,” without negating its necessity in any specific case.

Thus, we can only acknowledge that material reality is total, and there are no ways to escape from it. There are no loopholes, not because we haven’t found them yet, but because any newly discovered effect, no matter how fantastic or incredible it may seem at first, is inherently part of that very reality. Miracles do not occur, not because we are stubborn, narrow-minded materialists, but because the concept of a “miracle” contradicts itself.

The totality of informational reality

A discussion about the totality of material reality would be incomplete without adding a similarly valid consideration that we do not live in a material reality, but in an informational one, from which we cannot escape even a step or half a step.

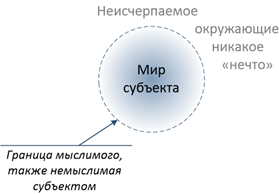

The world consists of things we know and things we don’t know. We can only operate with those things that we have at least some understanding of. What we know nothing about lies entirely outside the boundaries of our world. By learning something, we acquire things within our world. We expand the limits of our world. Whatever we consider a knowing subject, the very fact that it engages in knowledge (pushing the boundaries of the known) implies that the world of that subject is limited. Regarding the things that exist within the subject’s world, the subject can think (if, of course, it is capable of thought). However, concerning the things that lie beyond the subject’s world, it cannot think at all. It simply has no inkling about them. Interestingly, the boundary of the thinkable itself is also unthinkable. As Ludwig Wittgenstein rightly noted in the “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus,” in order to think about the boundary, one must think about things on both sides of it, but the things on the other side of the boundary of the thinkable are, by definition, unthinkable. Thus, it turns out that everything we can think about has already become information.

Let’s take a brick, for example. It exists. But it only exists for us if circumstances have aligned in such a way that it has become information for us. For instance, we saw it. Or we stumbled over it in the dark. Or someone told us about it. Ultimately, we are familiar with the concept of “brick,” and therefore all bricks exist within our world, including those we will never personally encounter in our lifetime.

All we can say about what lies beyond our world is this:

- It undoubtedly exists. In any discussion about existence, the key question is “where?” and in this case, there is an surprisingly simple and comprehensive answer to that question: beyond the conceivable.

- It is inexhaustible. That is, as long as there exists a knowing subject, the fact of its functioning clearly indicates that what lies beyond its conceivable understanding has not yet been fully explored.

- It has no properties other than the fact of existence and the fact of inexhaustibility. Any property can only be attributed to what is thinkable (attributing properties is one form of thinking). Attempting to assign any property to the unthinkable immediately introduces internal contradiction into the reasoning. In fact, even the properties of existence and inexhaustibility are derived not from knowledge of the, by definition, unknowable, but from the properties of the subject.

I call it a concept.information spacesuitEverything we have has already become information for us, obtained from the inner walls of our informational spacesuit. All our thinking (and only thinking, nothing more) that builds assumptions about the external world occurs inside the spacesuit, and the only way we can influence the undeniably existing, inexhaustible reality outside is by applying efforts (naturally, informational) to the inner walls of our spacesuit.

The picture turned out to be a bit frightening. It could even trigger a bout of claustrophobia. In reality, there’s nothing scary about this concept if we remember in time that inside our information spacesuit lies everything we know, value, love, aspire to, and even everything we hate. The whole world as we know it.

Thus, the informational reality is also total, and we know nothing of what is not information. At least because any knowledge is information that we possess. Naturally, this is within the informational spacesuit.

It should be noted right away that discussions about the limitations of the follower may initially seem like a meaningless collection of clichés. They are indeed meaningless only if a thinking and existing being is considered strictly as a singular entity. However, if there are at least two beings, the areas of the follower increase to more than one, and it turns out that:

- In the realm where worlds intersect, beings understand each other, and it is in this (and only this) realm that communication between them is possible.

- It can be assumed that theoretically, there could be a situation where the worlds of two different beings completely coincide, but one can probably only seriously expect to discover such a phenomenon in artificially created beings.

- From the perspective of any being, the world of any other being appears as a subset of its own world. A being is unable to grasp the boundaries of its own world, but the limitations of another being’s world are easily recognizable. For example, concepts such as “food,” “pain,” “joy,” “interesting,” “play,” and a vast number of others are common to both humans and dogs, but it is clear to us that the situation of “I can’t remember my email password” is entirely outside the dog’s world. The illusion of the boundlessness of one’s own world, combined with the obvious limitations of other beings, creates a fertile ground for all theories of superiority without exception.

- No creature can know anything about that part of another creature’s world that lies outside its own. One can only assume that this part exists. Or does not exist. Nothing is known. Nothing can be asserted about what lies beyond the realm of thought.

- Any activity of a being, justified by considerations that lie outside the framework of another being’s world, appears to that other being as unconscious activity. For example, when observing the quirky interactions of dogs at a dog park, we tend to interpret what is happening as a manifestation of instincts. However, if we think about it carefully, we can also attribute our own activities (including the most conscious ones) to the expression of instincts. The concept of “instinct” is one of those mental “crutches” we use to give a scientific veneer to discussions about things we do not understand.

- Beings that do not intersect with each other’s worlds appear to one another as inanimate phenomena of nature. This, of course, does not imply that everything we consider inanimate is actually animated. The “if” does not work in reverse.

The image of the interaction of worlds shown here is something we, humans, cannot observe, as a significant part of it lies beyond our human realm. Dogs cannot observe it either for the same reason. Perhaps a cat might perceive a similar picture, but of course, it does not fully observe either the human world or the dog world. If you thought that I was mistaken in depicting the dog’s world as a circle the same size as the human world, it only means that you have not yet fully grasped the understanding that it is impossible to make any assertions about things that lie beyond the limits of the conceivable.

Reflections on creatures and the worlds they inhabit are valuable to us not only for their own sake (they lead to quite valuable conclusions) but also as a way to practice applying the concept of the information spacesuit. This is the very concept that suggests that the informational reality is total, and there is no way for us to escape it.

The totality of the indivisibility of realities

Thus, we have obtained two total realities – the physical and the informational. It may seem that two is too many. One might want to reduce it to just one. For example, one could align with materialists and try to prove that everything boils down to matter. Or with idealists, to reduce everything to consciousness.

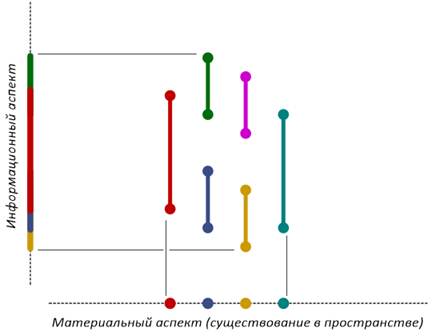

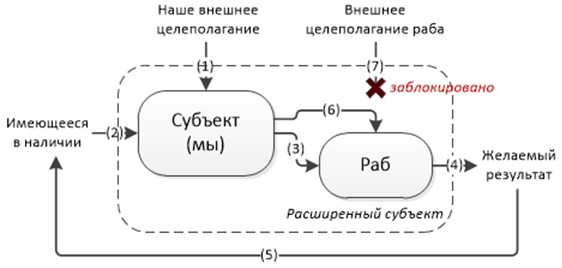

Take a look at the picture:

Like any schematic representation, the image should not be taken too literally. It is merely a visualization to aid understanding. Let’s say the object depicted in the picture is the book “Hamlet” in all its fullness and inseparable unity. But imagine that we have forgotten how to see this thing as it truly is, and we can only study projections. If we examine the material aspect (that is, the projection on the horizontal axis), we see atoms. When we shift to the vertical axis, we see a different projection—the intricate web of the plot—but at this point, the material aspect falls out of consideration. It becomes perpendicular to us. Of course, this may create the illusion that the world is divided into the world of things, which we acquire on the horizontal axis, and the world of ideas, which we acquire on the vertical axis. But this is, of course, just an illusion. The world is one. The differences arise only because we are unable to grasp the object in all its fullness.

In principle, it would be possible to do without an image. The total inseparability of realities automatically follows from the fact that both realities under consideration:

a) total

b) different

In fact, there are a number of objects whose informational aspect does not interest us, and therefore, when we think about them, we only consider the material aspect. For example, when I’m thirsty, I’m only concerned with the material aspect of the water I’m about to drink. And when I need to calculate the length of the hypotenuse using the two legs, I don’t even try to find that specific geometry textbook where I learned the Pythagorean theorem. It’s not always necessary to try to see every subject in all its complexity. That would be too costly. We need to be prepared for the fact that in the overwhelming majority of situations, a one-sided perspective is exactly what we need. However, while practicing this one-sided view, we must always clearly understand which “axis” (the vertical informational or the horizontal material) we are on.

The picture, of course, turned out to be clear and beautiful, but it still raises the curiosity of whether any of the axes is a descendant of another axis. It just can’t be that, long ago, at the beginning of time, two scales emerged simultaneously. Logically, something must have come first, and then the second must have crystallized from it. So here we are again, caught in the trap of discourse about first causes. It was mentioned earlier that there is no productive way to reason about the primacy of matter and consciousness, so let’s allow an instrumental approach to free us from having to engage with this question.

So, we have no choice but to honestly admit to ourselves that it makes sense to talk about two realities – the material and the immaterial. How they intertwine is a separate question, and we will learn to address it. For now, it is enough for us to understand that the immaterial aspect does not exist without the material, and the material without the ideal entirely falls into the realm of the unimaginable “something.”

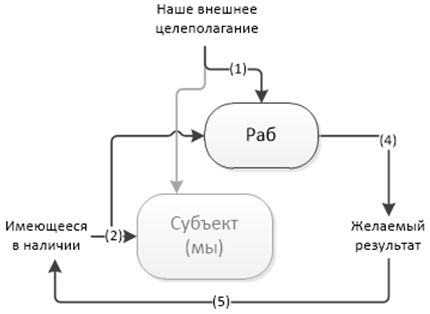

Reification

Reification is a logical error that occurs when we forget that the projection we are considering is a projection onto an informational “axis,” and we attribute to the elements of this informational projection properties that are only found in elements of a material projection. The reason for this is that our experience of interacting with material objects is incomparably richer than our experience of interacting with thoughts, ideas, and concepts. Our eyes look into the material world. The sounds we hear are produced by material objects. The things we touch are material. Therefore, when contemplating a non-material subject, we often try to visualize it in our mind’s eye, “feel” the argument regarding its stability, and figure out what the statement “smells” like.

Reification is such a common logical fallacy that it is rarely discussed. There isn’t even a specific word for it in the Russian language, and different texts refer to this issue using various terms. For instance, in the translation of Immanuel Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason” that I have, it is referred to as “hypostatization.” As of the time of writing this text, there is no corresponding article on this topic in the Russian-language Wikipedia.

What happens during reification can be illustrated with this image:

Instead of learning to work with abstract concepts, we wrap the informational aspect in material reality and end up with something concrete, visual, and easily digestible that is ultimately meaningless. Nothing good can come from attributing the existence of an object to a totality in which the object does not exist.

The main technique that can be used to avoid reification is to train yourself to pay attention to the existence of objects right away when reasoning about them.where exactlyThe object exists. So where is it?takes placeIf it is possible to clearly associate an object with physical space, one can confidently assert that it is a material object (that is, a projection of the object onto material reality). However, if answering the question “where?” requires some twisting and leads to strange responses, it is likely that we are dealing with an informational aspect.

Let’s practice a little:

- Where is my chair? Right under me. There is a clear spatial connection. Therefore, considering this particular chair as a material object is not reification at all.

- Where is the number 2? It’s a strange question. Essentially, it can be anywhere, depending on how you apply a ruler. You could go a bit crazy and assume that somewhere behind high fences lies a repository of mathematical truths, and there exists a standard for the number 2, but that’s not even funny. In despair, one might even suggest that the number 2 doesn’t actually exist, but that would be quite odd as well. We can find the correct solution to the equation “x + x = 4,” but what we found, according to our assumption, “doesn’t actually exist.” Of course, the number 2 does exist, and we can even say where it is: neatly positioned between the numbers 1 and 3 in the sequence of natural numbers. For the chair I’m sitting on, its container is physical space, while for the number 2, its container is the natural number line. Any other attempt to place the number 2 somewhere (for example, in some “world of ideas”) might provide a charming visual, but it wouldn’t make any sense. The natural number line (and so what if it’s also an abstraction?) is sufficient to answer the question “where does it exist?” in relation to the number 2.

- Where is my home? I can give two correct answers:

- There is an address. Exact geographical coordinates. When talking about a house in this context, we have a physical object that sometimes needs to be repaired with quite tangible tools – a hammer, a screwdriver, a spatula, and other household items.

- My home is where I am loved and awaited. Interestingly, such a place doesn’t necessarily have to have geographical coordinates. If I am loved and awaited in an online forum, then that is also my home. The response has become detached from physical space, and therefore we can state that in this case, we are talking about the projection of an object onto the informational axis.

- Where is Wikipedia located? Of course, there are data centers with servers where this thing is hosted. But for the vast majority of us, it’s unlikely that we’ll ever find ourselves at that exact location to access Wikipedia. It’s much simpler and faster to find it at the address “ru.wikipedia.org.” It seems to me that this string of characters bears very little resemblance to spatial coordinates.

- Where is “Hamlet”? It’s right there on the shelf. Yes, of course, but that’s only half the truth. There are other copies as well. Moreover, if any radio station is broadcasting a radio play of “Hamlet” right now (which is quite possible), then “Hamlet” can be picked up through the antenna.from any point in space“Any point in space” is not a spatial localization at all.

- Material objects exist in physical space. Okay. But where is physical space itself located? It cannot be located within itself. Perhaps it exists in a higher-order space? Maybe, but this assertion still doesn’t solve the problem, as it immediately raises the question, “Where is this hypothetical higher-order space?” The only honest option is to acknowledge that physical space is an abstraction. If you thought I was providing proof of the primacy of the ideal over the material, you were mistaken. I remind you that the question of primacy is entirely meaningless, as there is no situation in which it can be productively discussed.

- Does Harry Potter exist? And if so, where? Yes, he exists. In the story of Harry Potter. He is one of the central figures. You could say he is the main character, although opinions on that may vary. But physically, of course, he doesn’t exist anywhere.

- Does God exist? And if so, where? The naive child’s answer of “on a cloud” is obviously false, and almost any believer would confirm this. It turns out that any somewhat worthy answer to this question (“in the souls of the faithful,” “everywhere good is done,” etc.) bears little resemblance to spatial localization. Mystics of ancient times seemingly understood that the urge to reify God would be extremely strong, and thus they introduced a direct prohibition against any attempt to depict God in a physical form in the religions they created. Judaism and Islam have managed to maintain this prohibition, but Christianity, due to certain inherent characteristics, has not been able to avoid slipping into unrestrained reification of God. However, both Judaism and Islam have not completely escaped the reification of God. In both of these religions, God is subtly reified in the texts of their sacred scriptures. For Jews, this is most vividly expressed in their amusing “G-d,” while for Muslims, it manifests in the incredibly reverent attitude towards copies of the Quran and the direction towards Mecca.

The topic of “reification” requires a detailed discussion because “information” is one of those subjects that has been most heavily distorted by reification. We have become so accustomed to “transmitting” information from person to person, “storing” it on a disk, “keeping” it in our heads, and “processing” it on a computer that it appears to us as some kind of “subtle substance” that condenses somewhere, is stored somewhere, and travels from one point in space to another. This metaphor is so strong and obvious that it is difficult for us to imagine how we could do without this gross reification. Let’s return to our example with a book. If information is some kind of subtle substance condensing inside a book, then the printing press that produced it must have some devices that inject this “subtle substance” into the product. But we know exactly how books are made. Moreover, we know exactly how the machines that produce books are made. The printing press does nothing but arrange molecules of ink on the fibers of the paper. There is simply no “subtle substance.” If we want to learn to talk about information in a meaningful way, we must learn to discuss it without resorting to reification.

Chapter Summary

The first task that information philosophy must tackle is to eliminate the most insidious logical traps that hinder any productive dialogue about the existence of immaterial entities, namely:

- meaningless discourse on the primacy of matter or consciousness;

- the underdefinition of the concept of “matter”;

- habits of reification that immediately strip away any discussions about the immaterial.

The model object “book,” introduced at the beginning of the chapter, not only allows for a separate consideration of the material and immaterial aspects of reality but also offers some hints on how these aspects can be combined into a cohesive whole.

Key concepts and ideas:

- Material worldlike the world of things that exist in physical space.

- The immaterial worldlike the world of things, the localization of which in physical space is a logical error.

- Reificationas a logical error that involves attributing material existence to immaterial things.

- Reception.“Where does it exist?”This allows for a quick understanding of which aspect of reality is being discussed. If the conversation is about something that exists in physical space, then that thing is material. If the thing does not occupy space, then it is immaterial. In particular, the informational spacesuit mentioned in this chapter is a mental construct, and therefore, attempting to draw a line between the thinkable and the unthinkable somewhere in space is, in itself, a logical error.

- Information spacesuitThe subject is the totality of everything conceivable by the subject.

Chapter 2. The Existence of Information

Signals and Contexts

we must understand that the information itself is not contained within the book. Instead, it exists in the interaction between the reader and the text. The book serves as a medium that facilitates the transfer of ideas and knowledge, but the essence of the information is created in our minds as we engage with the content. Thus, while the physical object is necessary for the process, it is not the source of the information itself.to containA physical object cannot contain information within itself.

Let’s carefully analyze what happens when we read a book. Undoubtedly, there is a physical process involved, and some stages of reading a book are best described in physical terms. In particular, when we read a paper book with our eyes, it must exist as a physical object, and there must be an acceptable level of lighting. The optical system of the “eyes” must also be present and functioning properly. Using other methods of reading (Braille, text-to-speech programs) doesn’t significantly change the situation, and in these cases, it also makes sense to talk about a material component that must be present as well.

We can attempt to discuss what happens in our brains as readers after content is delivered in some way using physical terms, but this approach is not very promising. Something certainly occurs. The material component undoubtedly exists, but we currently lack the means to translate something as simple and obvious as “being surprised by an unexpected plot twist” into material terms. It’s possible that we may never have such a means. This is partly because the mechanism of being surprised by an unexpected plot twist may be realized differently in different minds.

The specificity of informational processes, unlike material ones, lies in the fact that the same informational process can be realized in fundamentally different ways “in matter,” while still remaining itself. For example, the sum of two numbers can be found using an electronic calculator, an abacus, counting sticks, a piece of paper and a pen, or even in one’s mind. The meaning and result of the action will remain the same. A book can be received in paper form by mail or in electronic form via email. The method of realization certainly affects many nuances, but the essence and meaning of what is happening remain unchanged. Any attempt to “ground” the informational process in a material component (“surprise is…nothing else“like the internal secretion of dopamine,” “ecstasy –”nothing else“like the internal secretion of endorphins” is akin to saying that the addition of two numbers is…nothing else…like the movement of wooden pieces along metal tracks. Material reality is total, so any informational process must have a material aspect; however, it cannot and should not be reduced solely to that, otherwise, the addition of numbers would have to become the exclusive prerogative of wooden counters. When we shift our focus to the informational aspect of what is happening, we need to be able to abstract from the material aspect, while, of course, understanding that it undeniably exists, but the specifics of it are not particularly significant to us.

Let’s continue examining the process of reading a book, abstracting from the details of the material realization of what is happening. For a reader to successfully read the text delivered to their receptors, a number of conditions must be met. First, they must know the language in which it is written. Second, they must be able to read. Third, they must understand why this activity is currently preferable to all others. It is not difficult to notice that all the listed conditions pertain to the reader’s possession of information, as “knowledge,” “skill,” and “understanding” are all synonyms for the concept of “information.” Thus, for reading a book, we have two sets of conditions for the successful progression of the process: the presence of a text delivered in some way and the reader’s prior preparedness. We will denote the condition of text delivery as the requirement for the presence of…signalWe will define the condition for the reader’s preparedness as the requirement for presence.contextТекст для перевода: ..

What’s important is that these same two sets of conditions are observed in any process we can identify as information acquisition. Even when considering something as simple as a remote-controlled car, it can only receive commands if, first, everything is in order with the delivery of the radio signal (the antenna isn’t broken and the car hasn’t rolled too far from the remote) and, second, the car’s control unit “understands” the commands sent by the remote. This means that even though everything seems to happen in a reliably deterministic “hardware,” a crucial component that ensured the successful reception of data by the receiver from the transmitter was the knowledge that the receiver’s designer gained from the transmitter’s designer. It is this knowledge that ensured that the receiver became a material object, where the atoms are arranged not randomly, but in a very specific way.in a special wayThe radio wave that reached the antenna is by no means all the information that entered the receiver. There may have also been an email received by the developer of the car’s control unit from a colleague working on the remote control.

Both components – andsignal, and.context“We can consider it from both a material and an informational perspective. However, while it is sometimes possible to abstract from the informational aspect of the signal (especially when the channel bandwidth is clearly excessive), it is impossible to abstract from the informational aspect of the context, which is essentially the ability to interpret the signal.”Context is the information about how to interpret a signal., and therefore we must consider it as an immaterial entity.

It may seem that transferring the mysterious immateriality into this enigmatic “context” involves a certain element of trickery. However, it is not difficult to notice that the information we perceive and the information that makes up the context are…differentInformation. The plot of a book and the knowledge of the language in which it is written are two different kinds of knowledge. If the resulting recursion of the structure (the existence of a second-order context requires a third-order context, and so on ad infinitum) raises some concerns, I would like to point out, just to jump ahead a bit, that this is not a defect of the signal-context structure, but probably its most valuable property. We will return to this topic in the fifth chapter to prove an extremely useful theorem through the recursion of the signal-context structure.

The significant advantage of considering information as the result of the interaction between a signal and its context, in addressing our metaphysical challenges, lies in the fact that this construct serves as the very bridge between worlds that we have been lacking. If, in a specific situation, we manage to abstract from the informational aspects of the signal (which is often not particularly difficult), we gain the opportunity to discuss the involvement of material objects in the informational process. If we also manage to examine the context in all its dual nature (which is quite common in our age of information technology), we end up with a full-fledged bridge between the material and informational worlds for that particular situation. It should be noted right away that the existence of this bridge still does not grant us the right to reify information. A signal, when viewed as a material object, can be reified (for example, a file saved on a flash drive, and the flash drive is in the pocket), but the context, meaning the ability to interpret the signal, cannot be reified.

When considering a classic situation of data transmission from the perspective of information theory, we have a transmitter that “places” information into a signal and a receiver that “extracts” information from it. This creates a persistent illusion that information exists within the signal itself. However, it is important to understand that interpreting a specially prepared signal is far from the only scenario for acquiring information. By paying attention to what is happening around us, we receive a great deal of information that no one has sent us. A chair does not send us information that it is soft, a table does not send us information that it is hard, the black ink on a page does not send us information about the absence of photons, and a turned-off radio does not send us information that it is silent. We are capable of understanding the material phenomena around us, and they become information for us because we already have a context that allows us to interpret what is happening. Waking up at night, opening our eyes, and seeing nothing, we extract the information that it is not yet dawn not from the presence of a physical phenomenon, but from its absence. The absence of an expected signal is also a signal, and it can be interpreted as well. However, the absence of context cannot serve as some special “zero” context. If there is no context, then there is no place for information to arise, no matter how much signal comes in.

We all know very well what information is (for beings living in an informational suit, it can’t be any other way), but we tend to consider only that part of it which is referred to here as “signal.” Context is something we take for granted, and so we habitually set it aside. By doing so, we are forced to confine all “information” solely to the signal, and in this way, we mercilessly reify it.

There’s nothing complicated about getting rid of the reification of “information.” You just need to learn to remember in time that, besides the signal, there is always context. The signal is merely raw material that gains meaning (value, usefulness, significance, and yes, informativeness) only when it enters the appropriate context. And context is something that must be discussed in non-material terms (otherwise, that discussion will definitely lack meaning).

Let’s briefly revisit the topic of “properties of information” and assess how these properties fit into the two-component structure of “signal-context.”

- Novelty.If the reception of the signal adds nothing to the informational aspect of the existing context, then the events of signal interpretation do not occur.

- Authenticity.The interpretation of a signal by context should not provide false information (“truth” and “falsehood” are concepts applicable to information, but not to material objects).

- Objectivity.The same as reliability, but with an emphasis on the fact that the signal may be the result of another context’s work. If the context trying to obtain information and the intermediary context do not have mutual understanding (primarily regarding their goals), then the information will lack reliability.

- Completeness.The signal is present, objective, and reliable, but it is not enough in context to obtain complete information.

- Value(usefulness, significance). There is a signal, but no suitable context. All the words are clear, but the meaning is not grasped.

- Availability.Signal characteristics. If a signal is impossible to obtain, then even the most wonderful and suitable context won’t help the information to emerge. For example, anyone could easily come up with ideas about what to do with accurate data on how tomorrow’s football match will end. But, unfortunately for many, this signal will only appear after the match is over, meaning its usefulness and significance will no longer be the same.

In my opinion, the properties listed above resemble more of a list of potential malfunctions than actual properties. Properties should describe what we can expect from the subject in question, as well as what we cannot rely on. Let’s try to derive at least a few obvious consequences from the “signal + context” construct, which will represent properties not of a specific piece of information, but of information in general:

- Subjectivity of information.A signal can be objective, but context is always subjective. Therefore, information by its nature can only be subjective. We can only speak of the objectivity of information if we have managed to ensure a unity of context among different subjects.

- The informational inexhaustibility of the signal.The same signal, when placed in different contexts, conveys different information. This is why, by revisiting a favorite book from time to time, one can discover something new each time.

- The law of conservation of information does not exist.It doesn’t exist at all. We like it when the objects we work with strictly adhere to the laws of conservation and are not prone to appearing out of nowhere, and even more so, they don’t have the habit of disappearing into nothing. Unfortunately, information does not fall into this category. We can expect that only signals can be subject to the laws of conservation, but within a signal, there is no information, nor can there be. We just have to come to terms with the idea that, in normal circumstances, information indeed comes from nowhere and goes nowhere. The only thing we can do to retain it in some way is to ensure the integrity of the signal (which is not a problem in itself), the context (which is much more complicated, as it is a variable thing), and the reproducibility of the situation in which the signal enters the context.

- Information is always the complete and exclusive property of the entity within the context in which it occurred.A book (a physical object) can belong to someone, but the thoughts generated by reading it are always the sole property of the reader. However, if we were to legalize private ownership of other people’s souls, we could also legalize private ownership of information. That said, this does not negate the author’s right to be recognized as the author, especially if that is the truth.

- A signal cannot be assigned characteristics that apply only to information.For example, the characteristic of “truthfulness” can only be applied to information, meaning the combination of a signal with its context. The signal itself cannot be true or false. The same signal, when combined with different contexts, can convey true information in one case and false information in another. I have two pieces of news for the followers of “book” religions: one is good, and the other is bad. The good news: their sacred texts are not lies. The bad news: they do not contain truths either.

To answer the question “where does information exist?” without using a two-component signal-context structure, one has to employ the following popular approaches:

- “Information can exist in physical objects.”For example, in books. When this approach is taken to its logical conclusion, one inevitably has to acknowledge the existence of “info-essence” – a subtle substance present in books beyond the fibers of paper and bits of ink. But we know how books are made. We know for certain that no magical substance is poured into them. The presence of subtle substances in the objects we use to acquire information contradicts our everyday experience. The signal-contextual construct functions perfectly well without subtle substances, while still providing a comprehensive answer to the question of “why the book itself is necessary for reading.”

- “The world is permeated by informational fields, in the delicate structure of which everything we know is recorded.”It’s a beautiful and quite poetic idea, but if that’s the case, it’s unclear why a volume of “Hamlet” is needed to read “Hamlet.” Does it function like an antenna tuned to a specific Hamlet frequency? We know how volumes of “Hamlet” are produced. We are certain that no detection schemes, set up to receive otherworldly fields, are embedded in them. The signal of contextual construction doesn’t require any assumptions about the existence of parallel invisible worlds. It manages perfectly well without these unnecessary entities.

- “Information can only exist in our minds.”A very popular idea. The most insidious and resilient variant of reification. Its insidiousness is primarily explained by the fact that science has yet to develop a coherent understanding of what happens in our minds, and in the darkness of this uncertainty, it can be convenient to hide any shortcomings in our thinking. In our large and diverse world, it sometimes happens that a person writes a work and then, before they can show it to anyone, dies. Years later, the manuscript is found in an attic, and people learn about something none of them knew all that time. If information can only exist in minds, how can it leap over the period when there is not a single mind that possesses it? The signal-contextual construct explains this effect simply and naturally: if the signal (the manuscript in the attic) has been preserved and the context has not been completely lost (people have not forgotten how to read), then the information is not lost.

Let’s take a look at how the idea of signals and contexts fits into what happens during the transmission of information. It seems that something remarkable should occur: on the sender’s side, there is information, then the sender transmits a signal to the receiver that contains no information, and on the receiver’s side, the information is present again. Let’s assume Alice intends to ask Bob to do something. It’s important to note that Alice and Bob do not necessarily have to be real people. For instance, Alice could be a business logic server, while Bob could be a database server. The essence of what is happening does not change. So, Alice has information, which is, of course, a combination of signal and context within her. With this information, as well as knowledge of what signals Bob can receive and interpret, she makes some change in the physical world (for example, writing a note and sticking it on the refrigerator with a magnet, or if Alice and Bob are servers, utilizing the network infrastructure). If Alice is correct about Bob, then Bob receives the signal within his existing context and gains information about what he should do next. The key point is the commonality of context. When we talk about people, this commonality is ensured by having a shared language and being involved in joint activities. When we talk about servers, the commonality of contexts is realized through compatibility of data exchange protocols. It is this commonality of contexts that allows information to seemingly leap over the segment of the path where it cannot exist and appear on the receiver’s side. Generally speaking, information does not actually leap anywhere. The fact that Alice possesses…the sameThe information that Bob can only be discussed if they have indistinguishably identical signals and indistinguishably identical contexts. In human life, this never happens. To see the color green.alsoIt is impossible to see him as another person does, but it is possible to come to an agreement between ourselves that…Text for translation: such.We will denote the color among ourselves with the signal “green.”

The signal-context construction is not entirely new to world philosophy. Even 250 years ago, Immanuel Kant wrote that “our knowledge (information?) although it stems from experience (signal?), but it is completely impossible without the presence of a priori knowledge in the knowing subject (context?)»..

Measurement of information

Measuring information in bits is a favorite pastime. One cannot resist the pleasure of pondering this, while also applying the counting method to the signal-context structure that has become familiar to us and, hopefully, understandable.

If we recall the classical theory of information, the generalized formula for calculating the amount of information (in bits) is as follows:

where.n.– the number of possible events, andp.n.– probabilityn.Let’s consider what each part of this formula means from the perspectives of the receiver and the transmitter. The transmitter might report, for example, on a hundred events, where the first, second, and third events each have a probability of 20%, while the remaining 40% is evenly distributed among the other ninety-seven events. It’s not difficult to calculate that the amount of information in the report about one event from the transmitter’s perspective is approximately 4.56 bits:

I.= — (3 × 0.2×log2.(0.2) + 97 × (0.4/97)×log2.(0.4/97)) ≈ — (-1,393156857 — 3,168736375) ≈ 4.56

Please don’t be surprised by the fractional result. In engineering, it’s common to round up in such cases, but the exact value is often interesting as well.

If the receiver knows nothing about the distribution of probabilities (and how could it?), then from its perspective, the amount of information received is 6.64 bits (this can also be easily calculated using a formula). Now let’s imagine a situation where the receiver is only interested in events number 1 (“execute”), 2 (“pardon”), and 100 (“award an order”), while everything else is just uninteresting “other.” Let’s assume the receiver already has statistics from previous episodes and knows the probability distribution: execute – 20%, pardon – 20%, award an order – 0.4%, other – 59.6%. Calculating this, we get 1.41 bits.

The variation turned out to be significant. Let’s look for an explanation for this phenomenon. If we remember that information is not just a single objectively existing signal, but a combination of “signal + context,” it becomes quite clear that the amount of information generated when receiving a signal should also be context-dependent. Thus, we have a good alignment between the signal-context concept and the mathematical theory of information.

Magnitude“I”.The value calculated using the formula discussed is typically used to solve the following problems:

- For constructing a data transmission environment. If the coding task is formulated as “give everything you have, but do it as efficiently as possible,” then when solving it for the case described in the example, one should aim for a value of 4.56 bits. This means trying to ensure that, on average, a million transmission cycles fit as closely as possible into 4,561,893 bits. One should not expect to compress it into a smaller volume. The math is unforgiving.

- To understand how much the uncertainty of the receiver decreases upon receiving a signal, it is assumed that the arrival of information reduces the informational entropy of the receiver by the amount of that information. If we consider the amount of information in this sense, the correct answers, depending on the properties of the receiver, will be 6.64 and 1.41 bits. The value of 4.56 will also be a correct answer, but only if the receiver is interested in all events and their probabilities are known in advance.

In the overwhelming majority of cases, when we talk about bits, bytes, megabytes, or, for example, gigabits per second, we are referring to the first interpretation. We all much prefer using broadband Internet over a sluggish dial-up connection. However, there are times when we find ourselves spending half a day online, reading a mountain of texts and watching a ton of videos, just to finally get a simple binary answer to our question in the form of “yes or no.” In this process, our uncertainty decreases not by the dozens of gigabytes we had to download, but by just one bit.

The entropic interpretation of the nature of information raises more questions than it answers. Even from a purely everyday perspective, we see that the least uncertainty is found among those citizens who have never read a single book, and whose cognitive interactions with the outside world are limited to watching TV series and sports broadcasts. These respected individuals exist in complete, blissful certainty regarding all conceivable questions of the universe. Uncertainty only arises with the broadening of one’s horizons and the acquiring of the detrimental habit of pondering. The situation where acquiring information (reading good, intelligent books) increases uncertainty is impossible from the standpoint of the theory of information entropy, but from the perspective of signal-context theory, it is quite a common phenomenon.

Indeed, if the result of receiving a signal is the creation of a new context, then we need more and more signals to sustain it, which will satisfy this context but may also inadvertently create a new, originally hungry context. Or even several of them.

The discussions about how information might be related to order are equally surprising (if entropy is a measure of chaos, then negentropy, or information, should be a measure of order). Let’s consider the following sequences of zeros and ones:

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000An ideal order in the “dream of a hostess” style. But there is no information here, just like there is none on a blank sheet of paper or a freshly formatted hard drive.1111111111111111111111111111111111111111Essentially, the same thing.0101010101010101010101010101010101010101It’s already more interesting. The order remains perfect, and there’s still not much information.0100101100001110011100010011100111001011I didn’t hesitate to toss a coin. 0 – heads, 1 – tails. I tried to throw it fairly, so we can assume that it resulted in perfect randomness. Is there any information here? And if so, what is it about? The answer seems to be “about everything,” but if that’s the case, how can we extract it in a usable form?1001100111111101000110000000111001101111Similar to a coin, but using a pseudorandom number generator instead.0100111101110010011001000110010101110010It also seems like the same kind of random nonsense, but it’s not. I’ll explain what it is below.

If we remove the text comments and pose a riddle about what could result from flipping a coin, the first three options would be immediately ruled out. The fifth option is also suspicious because there are more ones than zeros. This reasoning is flawed. With a fair coin toss, the probability of all these outcomes is the same, equal to 2.-40.If I continue to flip a coin without sleep or rest in the hope of reproducing at least one of the six presented outcomes, I can expect that if I’m lucky, I might succeed in about a hundred thousand years. However, it is impossible to predict which specific outcome will occur first, as they are all equally likely.

The sixth item, by the way, presents the word “Order” in eight-bit ASCII code.

It turns out that information is neither in perfect order nor in perfect chaos. Or is it? Imagine that a perfectly chaotic sequence of zeros and ones (No. 4) was generated not by me, but by an employee of the enemy army’s encryption center, and is now being used as part of a secret key to encrypt messages. In this case, those zeros and ones immediately stop being meaningless digital junk and become super important information for which codebreakers would be willing to sell their souls. It’s no surprise: the signal has gained context and, as a result, has become quite informative.

I have no desire to claim that the entropy theory of information is completely incorrect. There are several specialized applications where it yields adequate results. It is important to clearly understand the limits of its applicability. One possible limitation could be the requirement that the received signal does not lead to the formation of context. In particular, most communication tools meet this criterion. It is indeed possible to discuss the separation of signal from noise as a struggle against entropy.

The measurement of information has another aspect that is worth remembering. The result of any single measurement is a number. In our case, this is bits, bytes, gigabytes. Once we have a number, we typically expect to manipulate it in familiar ways. We compare it as “greater/less,” add, or multiply. Let’s consider two examples of applying the operation of “addition” to quantities of information:

- There are two flash drives. The first one is 64 GB, and the second one is 32 GB. In total, we have the capacity to store 96 GB on them. That’s right, everything is fair and accurate.

- There are two files. The first one is 12 MB, and the second one is 7 MB. How much information do we have in total? One might be tempted to add them up and get 19 MB. But let’s not rush. First, let’s feed these files to a compressor. The first file was compressed to 4 MB, and the second to 3 MB. Can we now add the numbers and get the total?trueWhat is the volume of the available data? I would suggest not rushing and taking a look at the contents of the original files. We see that all the content of the second file is present in the first file. This means that adding the size of the second file to the size of the first file doesn’t make any sense. If the first file were different, then the addition would be meaningful, but in this particular case, the second file doesn’t add anything to the first.

From the perspective of the amount of information, the situation with quines—programs that have the ability to output their own source code—is quite interesting. In addition to this function, such a program can contain something else: a useful algorithm, texts, images, and so on. This means that within the program, there is this “something else,” and on top of that, it contains itself, encompassing its entire self once again along with that “something else.” This can be expressed with the formula: A = A + B, where B is not equal to zero. Such an equality cannot exist for additive quantities.

Thus, the situation with the amount of information is quite strange. One could say that the amount of information is a conditionally additive quantity. In some cases, we are allowed to add the existing numbers, while in others, we are not. When it comes to the capacity of a data transmission channel (in particular, a flash drive can be considered a channel for transmitting data from the past to the future), addition is valid. However, when “weighing” a specific signal, we obtain a quantity whose ability to be added to other similar quantities is determined by external factors, the existence of which we may not even be aware of. For example, we can talk about the informational capacity of the human genome (DNA can be viewed as a medium for data transmission, and as far as I know, there are research groups trying to construct storage devices based on DNA), and it is approximately 6.2 Gbit, but any answer to the question“How much information is specifically recorded in my genome?”It would be meaningless. The most that can be asserted is that, regardless of the counting method used, the result cannot exceed those 6.2 Gbps. Or, if reality is such that we need to consider not only the sequence of nucleotide bases, then it might. However, if we talk about the total amount of information contained in a living cell, it seems that the answer to this question cannot be obtained at all, at least because the cell itself is a living organism, not a medium for data transmission.

In conclusion to the topic of “measuring information,” I would like to introduce the concept of “information class,” which allows us to assess the volume of information, if not quantitatively, then at least qualitatively:

- Final informativeness– a situation where all the necessary contextual signals can be encoded in a discrete sequence of finite length. It is precisely for such situations that measuring information in bits is applicable. Examples:

- The text of “Hamlet.”

- All the texts that have ever been created by humanity that have come down to us.

- Information in the genome.

The current information technologies work specifically with finite informational capacities.

- Infinite informativeness– A situation where a discrete sequence of infinite length is required to encode a signal, and any limitation (“lossy compression”) to a finite length is unacceptable. An example: data about the positions of balls that need to be preserved for perfect billiard simulation, so that if the process is later run in reverse, the original position is restored. In this case, the speeds and positions of the balls must be recorded with infinite precision (an infinite number of decimal places) because, due to the strong nonlinearities present, any error in a single digit tends to accumulate and lead to a qualitatively different result. A similar situation arises when numerically solving nonlinear differential equations.

Despite the seemingly outrageous nature of this idea, there are no fundamental reasons why, with the advancement of technology, we shouldn’t acquire means to work with infinite amounts of information.

- Unresolvable informativeness– a situation in which the required data cannot be obtained in any way due to fundamental limitations, either of a physical or logical nature. Examples:

- It is impossible to know what happened yesterday on a star that is 10 light-years away from us.

- It is impossible to know both the momentum and the position of a particle with absolute precision at the same time (quantum uncertainty).

- In a decision-making situation, the individual cannot know in advance which specific alternative they will choose. Otherwise (if the decision is known to them), they are not in a decision-making situation.

- A complete deterministic description of the universe cannot be obtained in any way. This is countered by a whole range of fundamental limitations—both physical and logical. Additionally, there are effects related to the barber paradox.

If there is still some hope regarding physical limitations that clarifying the picture of reality might allow us to translate some seemingly insurmountable informational constraints into finite or at least infinite ones, then logical limitations cannot be overcome by any advancement in technology.

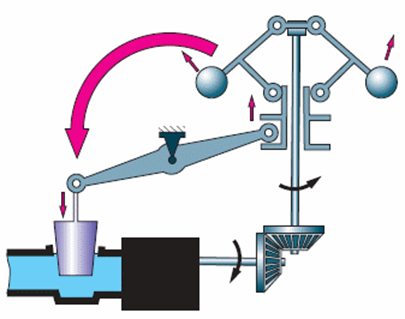

“Information” in physics

Historically, the connection between the themes of “information” and “entropy” arose from discussions about Maxwell’s demon. Maxwell’s demon is a fictional creature that sits by a door in a wall separating two parts of a gas chamber. When a fast molecule comes from the left, it opens the door, and when a slow one comes, it closes it. If a fast molecule comes from the right, it closes the door, but if a slow one comes, it opens it. As a result, slow molecules accumulate on the left, while fast ones gather on the right. The entropy of the closed system increases, and with the temperature difference generated by the demon, we can delightfully operate a perpetual motion machine of the second kind.

An eternal engine is impossible, and therefore, in order to align the situation with the law of conservation of energy, as well as with the law of non-decreasing entropy, it was necessary to reason as follows:

- When the demon is at work, the entropy of the gas decreases.

- However, since the molecules interact with the demon, the gas is not an isolated system.

- The system “gas + demon” should be considered as an isolated system.