Source текста.

Author. Ilya Simenko

Every person has an inherent right to keep secrets. A personal, inviolable informational territory that is off-limits to outsiders. Where is the boundary of this territory? The answer is always subjective. It depends on one’s profession, social status, the society itself, and the individual’s character. When the territory of privacy expands or contracts, it gets worse in some places and better in others. At the extremes, the negatives clearly outweigh the positives. If the territory is reduced to zero, a person is as exposed and defenseless as a laboratory rat in a numbered cage. If everything is shrouded in secrecy, a person becomes infinitely lonely and almost all the benefits of modern civilization are inaccessible to them. Somewhere between these poles lies an optimum. The most advantageous point in terms of comfort and safety.

Why do we protect our territory? What makes us feel uncomfortable when our secrets are revealed? We fear that others will harm us by knowing our secrets. They might steal, mock, or strike at our most vulnerable points. If there’s no way to cause harm, there’s no point in keeping a secret. If you live in a country with low crime and corruption rates and reasonable, moderate taxes, there’s no need to worry about hiding your income. If you’re surrounded by people who don’t care about your religious beliefs or sexual preferences, there’s no need to pretend to go (or not go) to church and to carefully display “high morals.” If in your country the outcomes of all elections are not known in advance, and journalists who publish scathing critiques and meticulous investigations about presidents and ministers are all alive, well, and free, then there’s no reason to hide your low opinion of the intelligence and morality of the current government.

So, privacy has no value in itself. It is only important under unfavorable external conditions. In tropical countries, people manage with almost no clothing at all. Closer to the poles, they bundle up in several layers. Notice! Clothing is the simplest and most obvious, yet at the same time the most inconvenient and unpromising way to combat the cold. It gets in the way, sometimes constricts, and limits movement (just like the hassles of encryption, keys, and passwords!).

How else can one stop suffering from the cold? One option is to move to warmer places, essentially escaping from unfavorable conditions. However, this is not always possible or practical. Another option is to build a warm house, which means partially changing the conditions. You could also start hardening your body and reduce the amount of clothing you wear, which would change your reaction to external conditions. All three of these methods require significantly more effort at the beginning and come with risks, but they offer a much more sustainable and comfortable solution in the long run.

Internet security is very much like clothing in our climate metaphor. Encrypting, blocking, password-protecting, and restricting access—these are all ways to bundle up warmly. All of this is undoubtedly necessary and important. It’s impossible to completely forgo “clothing.” However, we must not forget that all of this is, in a sense, an emergency, temporary measure. Much greater security and comfort in the future can only be achieved by addressing the source of the threat itself or by making ourselves immune to the threat without any additional protection.

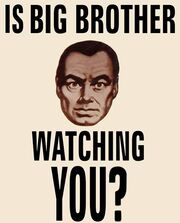

What does this mean in terms of information security? The biggest boogeyman of the modern internet is Big Brother. Governments, payment systems, intelligence agencies, Google, Facebook, Amazon, VKontakte are watching you! You can’t hide from them! But should you? Boycotting them, encrypting your data, hiding—these are fundamentally losing strategies.

Once, I was filming a news segment about how elephants were brought to the circus. Several enormous four-ton creatures spent many hours cramped in a tight trailer. They were quite unhappy. Each of them could easily crush a person like a bug, but five trainers managed to herd the elephants into their enclosure and calm them down in just a few minutes by offering them a basin of sweet wine. The elephants only expressed their displeasure vocally (Have you ever heard elephants roar? From five meters away? Without a barrier? An unforgettable experience! After a sip of sweet wine from the road and a snack, they rumble contentedly. It’s something between a kitten and a tank).

If trainers started running away from elephants at the first sign of disobedience, it wouldn’t end well. But they acted in unison and without panic. They knew the animals’ behavior and temperament well. And most importantly, the elephants also knew their trainers. After all, these are the people who feed them, take care of them, and play with them. An elephant is an intelligent animal; it won’t harm those it depends on without a serious reason.

The same goes for the “Big Brothers.” They are big and strong, but they depend on us just as much as we depend on them. If we completely avoid them—what, are we supposed to live in the woods? If we are afraid and hide, they will find us anyway if they need to. We can and should cooperate with them. But we need to keep them in check. We are the ones who feed and support them. They should be the ones who fear us. Of course, if they get out of hand and start taking too many liberties, sometimes it’s better to arm ourselves with cryptography and anonymous proxies, but we can’t stop there. Although the temptation is great. It’s uncomfortable for us to leave our familiar high-tech cocoon and seek solutions beyond algorithms and protocols. Politics, protests, manifestos—none of that is for us. We’d rather just encrypt ourselves better and that’s it. “Chirp-chirp, I’m in my little house!” So for the majority of the guarantees of our privacy (and indeed any of our rights and protections), we owe thanks to the “crowd of hamsters” who weren’t afraid to start a strike somewhere, to take to the streets in protest, and to force governments and corporations to behave decently.

What’s wrong with Google or Facebook owning a ton of information about my activities and interests, if I can be sure that if they misuse this information, they will lose a thousand times more than they gain? Their reputation relies on the fact that they don’t disclose my secrets to just anyone.

If advertising is absolutely unavoidable, then it’s better to have small, targeted messages, which might even include a useful link, rather than twenty irrelevant banners that I would have to see, even if they didn’t collect personal information.

Instead of hiding ourselves, it’s better to strive for states and corporations to have fewer secrets from us. Do you want to have a complete dossier on us? Fine, but please don’t hide your own activities. Even now, the need to publicly report, document, and provide citizens and shareholders with information about their work significantly restricts the hands of unscrupulous “servants of the people.” If they have more information about me, then I should have more information about them to ensure that no one is abusing the knowledge of my secrets. This is a fair exchange.

Throughout history, servants have known a great deal about their masters’ habits. Nowadays, machines have replaced our servants. Here it is. Through simple calculations, it has been shown that the modern European spends an amount of energy equivalent to the labor of a hundred slaves each year to meet their needs. The same applies to the internet. How many man-hours would it take to manually compile a list of links on any topic that Google provides in just a few milliseconds? By opening up part of our personal information space, we gain numerous advantages. What good are servants who do not know the tastes and routines of their master? Anything can happen; servants can betray or rebel, but we must assess the threat realistically. On a construction site, safety protocols must be followed, but walking down the street in a hard hat is a bit excessive. Although, yes, theoretically, something could fall on your head.

I want to have as few secrets as possible. Behind every secret lies some kind of trouble. I come up with complicated passwords not because I enjoy it, but because the threat of account hacking is very real. I would love to access my email inbox like I do the main page of Habr, without any authorization. I wish I could kick open the door to my apartment when my hands are full. Life without secrets is much more pleasant.

That’s exactly why most people are so careless about information security, driving cautious admins to the brink of hysteria. Yes, as a rule, they…toocarefree. But also fighters for privacy and control over their own information.tooworried. Geeks generally belong to the second category. After all, unlike most people, we are acutely aware of how tenuous access control to “closed” information really is. Everything literally relies on a handshake or a byte somewhere in the server code. That’s why we are so obsessed with the ideas of cryptography, decentralization, and host-proof systems. Meanwhile, the people around us look at yet another project for a decentralized secure social network and think:

— So how is this better than Facebook?

— How is that possible!? This is complete control over personal data!

— Well, I can edit my data myself anyway…

— No! That’s not it! They are all stored in the evil corporation’s data center.

— What do I care? Look, my salary is on a card too, not in a drawer, so what? Everything works, everyone’s happy, just back off!

That’s it. To “push through” safe decentralized technologies, it’s not enough to have the stick of “Big Brother.” You need a carrot. BitTorrent succeeded in this because downloading anything quickly for free is cool, and everyone understands that. Only by offering clear and appealing advantages can you make a protocol and the software based on it mainstream. The perceived territory of privacy, the area where the fear of losing control outweighs the discomfort of using security measures, is much smaller for the average person than for a techie. Wrap safe and cryptographically secure technology in a nice and user-friendly package, provide a set of useful, affordable, and preferably unique features, as the creators of Skype did, and people will start using that technology.

But every time we successfully defend another corner of our private lives, we should consider how to make it so that there’s no need to defend it at all. So that future generations will be amazed by our stories about how it once made sense to hide our address and phone number, sexual orientation, political and religious views, or the balance in our bank accounts. So that they look at us the way we currently look at this lady from the 19th century:

What, you don’t see anything unusual about her? She’s in a swimsuit!